Beyond The Movies: The True Story Of Grand Duchess Anastasia

The story of Grand Duchess Anastasia possibly escaping her murder has been immortalized in pop culture, but few know the true story of her tragically short life.

The life of Grand Duchess Anastasia of Russia was tragically cut short when she was only 17 years old, leading to rumors of her possible survival. Over a century later, she’s a pop culture icon.

The truth is that Anastasia was a fascinating girl who didn’t have the chance to grow up. Alongside her older sisters and younger brother, she’s been immortalized as a beautiful, young, and carefree girl in a beautiful white dress in a black-and-white photograph. Fact and fiction are often blurred together, leading many to know nothing about her life other than how she died. The truth is that her life is fascinating and worth learning about.

This is the true story of Grand Duchess Anastasia and how she became a legend.

Anastasia’s Early Life and Personality

Born on June 18, 1901, Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanova was the fourth and youngest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and his wife, Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna. While the birth of a healthy baby is usually a cause for celebration, Anastasia's birth was a disappointment to the Russian monarchy. Due to the Pauline Laws of Succession, a daughter couldn’t inherit the throne, leaving her parents without an heir after having four daughters.

Despite the rocky start, she was loved by her family and grew into a lively and vivacious girl. Known as the entertainer, she had a mischievous sense of humor and charming personality. In his memoir, Thirteen Years at The Russian Court, her French tutor Pierre Gilliard described her as “very roguish and almost a wag. She had a very strong sense of humor, and the darts of her wit often found sensitive spots. She was rather an enfant terrible, though this fault tended to correct itself with age. She was also extremely idle, though with the idleness of a gifted child. Her French accent was excellent, and she acted scenes from comedy with remarkable talent. She was so lively, and her gaiety so infectious, that several members of the suite had fallen into the way of calling her ‘Sunshine,’ the nickname her mother had been given at the English Court.”

Her personality is shown in the thousands of photographs she either took herself or family members took of her. One of her most famous photographs is her taking a selfie in the mirror, which she wrote about in her diary. She wrote, “I took this picture in the mirror, and it was hard because my hands shook… well, I made a stain [on the letter] because Olga butted in…Yes sirree!…Olga is hitting Marie, and Marie is screeching, like a foolish Dragoon, such a big fool.”

Anastasia was educated by tutors and spent the majority of her time with her sisters, Olga, Tatiana, and Maria. Of her sisters, she was closest to Maria, with whom she shared a bedroom and who was two years her senior. The two girls were different, as Maria was an ardent rule follower, but the sisters complemented each other’s personalities well.

Anastasia’s younger brother, Alexei, was born on August 12, 1904. While the Romanov family was delighted to celebrate the birth of an heir to the Russian throne, the celebration was short-lived when he was diagnosed with hemophilia, a genetic disorder that prevented blood from clotting properly. A simple cut or bruise could leave Alexei in severe pain and could lead to a life-threatening situation, causing the Romanovs to take extreme measures to protect him. Of his four sisters, Alexei was closest to Anastasia, who liked to spend her free time trying to cheer him up.

Teenage Years and the Russian Revolution

Anastasia was only 13 when World War I broke out in 1914, making her too young to volunteer as a Red Cross nurse. While her mother and two oldest sisters volunteered, Anastasia and Maria spent their time visiting wounded soldiers in hospitals to lift their spirits. According to Peter Kurth, historian and author of Anastasia: The Riddle of Anna Anderson, both girls thoroughly enjoyed visiting soldiers and spent much of the time asking them about their families and playing games like billiards or checkers. One soldier remembered Anastasia fondly for her “laugh like a squirrel.”

In March 1917, a revolution broke out in Russia. Anastasia was sick with measles when Nicholas was forced to abdicate the Russian throne. The family was put under house arrest in their palace outside St. Petersburg, where Anastasia and the rest of her family remained comfortable until they were shipped to Tobolsk, Siberia.

The family remained in Tobolsk until they were relocated to the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg in the spring of 1918. This was the last time that her French tutor, Pierre Gilliard, ever saw the Romanovs. In his memoir, he wrote, “How little I suspected that I was never to see them again, after so many years among them, I was convinced that they would come back and fetch us and that we should be united without delay.”

On July 17, 1918, Anastasia, her family, the family doctor, and three servants were awakened to be told they were switching locations. However, they were moved to the cellar of the Ipatiev House, where all 11 of them were brutally murdered. Anastasia was only 17 years old.

What About Rasputin?

In the 1997 animated children’s film Anastasia, audiences are introduced to a mysterious, creepy, and terrifying villain, Rasputin. While it’s obvious that he didn’t have superpowers or rise from the dead, the truth about Rasputin is stranger than fiction.

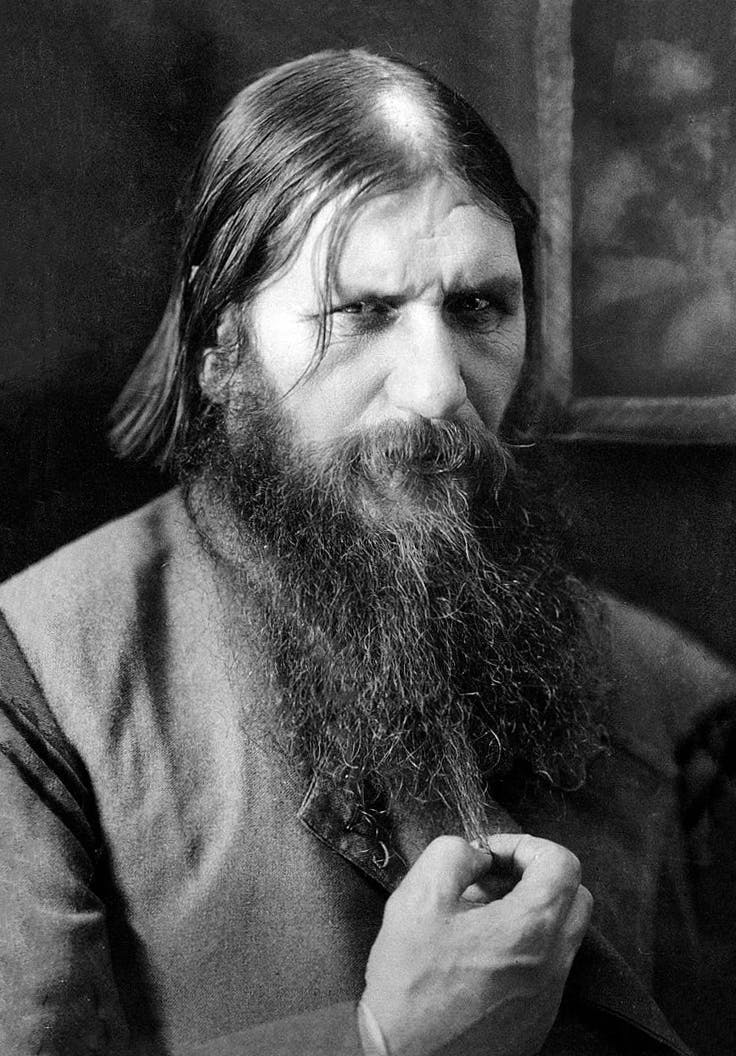

Since Alexei’s hemophilia could be fatal and cause a succession crisis, Nicholas and Alexandra sought help from an unorthodox source: a mysterious monk named Grigori Rasputin. To call Rasputin controversial and divisive would be an understatement. In 1897, he left his wife, children, and home village in Siberia to pursue a religious pilgrimage, and many believe he joined a religious sect outside the traditional Russian Orthodox Church known as the Khlysty. The Khlysty believed that “the best way to be closer to God was through sinful actions, especially those of the flesh.” It’s also believed that he practiced his “mystical healing powers” during his travels and spread the word of the Khlysty.

His travels landed him in the Russian capital of St. Petersburg, enchanting the minds of the nobility with his mysterious powers. He eventually caught the attention of Nicholas and Alexandra in 1905 and learned the truth about Alexei’s condition. Rasputin’s presence seemed to calm Alexei and lessen his bleeding, leading the Romanovs (mainly Alexandra) to believe that he had the power to heal Alexei. We now know Alexei likely bled less because Rasputin told doctors to stop giving him medicines like aspirin (which is a blood thinner), but the lack of medical knowledge in the early 20th century made it look like a miracle.

There were two sides to Rasputin. He appeared to be a holy man around the Romanovs but was depraved in public. He allegedly “pulled down his trousers and, as one eyewitness put it, waved his ‘reproductive organ’ in a restaurant,” leading many to wonder how he was behaving around the Romanovs, particularly Anastasia and her sisters. Despite rumors, there is no evidence that Rasputin ever sexually abused any of the Romanovs.

Rasputin’s ability to “heal” Alexei gained him so much favor with Alexandra that he was one of her top advisors during World War I while Nicholas was away at the front. With no political experience, Rasputin’s influence was disastrous. In December 1916, nobleman Prince Felix Yusupov decided to take matters into his own hands. He was joined by Nicholas’s cousin Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich and three other friends, including a doctor. The five men fed Rasputin poisoned wines and cakes, only to be surprised that it had no effect on him. The men tried to correct their mistake by shooting him, only to be surprised for him to survive that too. The third time was the charm when they threw him into the frozen Neva River, where Rasputin drowned.

How Anastasia’s Death Turned Her into a Legend

While DNA evidence confirmed that there were no survivors of the Romanov murders in 2007, the legend of a possible survivor lived on for nearly a century following the massacre of the royal family. With rumors of one of the Romanov children possibly surviving the massacre, it didn’t take long for imposters to show up. The most famous imposter, Anna Anderson, convinced many that she was Anastasia, and the legend of the lost princess was born.

In 1920, a young woman jumped into the Landwehr Canal in Berlin and was sent to the Dalldorf Asylum. With mysterious injuries and no knowledge of her past, she was dubbed “Madame Unknown” by doctors, nurses, and other patients. When a former noblewoman named Clara Peuthert became a patient at Dalldorf, she suspected that the mysterious young woman was one of the Romanov daughters. She was visited by Captain Nicholas von Schwabe, a former guard to Anastasia’s grandmother, the Dowager Empress, who showed her pictures of the Romanov family. When she said that the woman in the picture was her grandmother, she seemingly confirmed that she was a Romanov. One of Alexandra’s former ladies-in-waiting had doubts, claiming she was “too short to be Tatiana.” When the young woman said she never said she was Tatiana, many believed she meant that she was Anastasia.

The woman started to go by Anna Anderson, and the reaction from Romanov family members and friends was mixed. Many believed she was a fraud, while others believed she was Anastasia and that she deserved access to the Romanov fortune, but the evidence regarding her identity was inconclusive. Despite insufficient evidence, Anna spent much of her life being cared for by people who believed she was Anastasia. Anna Anderson died in 1984, still maintaining her identity as Grand Duchess Anastasia.

In 1927, another explanation for Anna Anderson’s identity emerged: Anna was really Polish factory worker Franziska Schanzkowska, who had been injured in a factory accident and gone insane, before disappearing. This explained her mysterious injuries and amnesia. After Anderson’s death in 1984, her DNA was analyzed and compared to the five skeletons found that were believed to be the Romanovs – the conclusion was that Anderson was probably not Anastasia. After two more skeletons were found in 2007, believe to be the rest of the Romanov family, Anderson’s claims were seemingly disproved. It’s nearly impossible to tell if she truly believed that she was Anastasia, was a grifter, or was so overwhelmed by the support she received that she went along with it.

Anastasia in Pop Culture

It didn’t take long for the story of Anastasia’s possible escape to get the Hollywood treatment. Anna Anderson’s story was the inspiration behind the 1956 film, Anastasia, starring Ingrid Bergman and Yul Brynner. This film portrays Anastasia as a mysterious woman with amnesia who proves her identity to the Dowager Empress. The 1997 animated musical children’s film, Anastasia, tells a similar story with elements of fantasy, including a curse that suspends Rasputin between life and death when he fails to kill Anastasia.

The animated film was the primary inspiration behind the 2017 Broadway musical Anastasia, which features many of the songs from the 1997 film. The main difference is that there are no elements of fantasy, and the villain is a Bolshevik official, not Rasputin.

While these stories don’t tell a perfectly accurate depiction of Anastasia’s life, they do a good job of keeping her story and the story of the Romanovs alive. Historical figures that are heavily portrayed in pop culture, like Cleopatra and Marie Antoinette, are remembered for centuries after their deaths thanks to storytelling, and the legend of Anastasia has kept her alive for over a century since her death.

Closing Thoughts

While the movies and musicals that portray her life do a good job of showing Anastasia’s fun and carefree personality, they’re not historically accurate portrayals of her life. The truth is that her story (and much of Russian history) is worth learning about, as it provides a fascinating window into the past.

Support our cause and help women reclaim their femininity by subscribing today.