Many Americans Think They Would Have Been Abolitionists In The South Pre-1860. They’re Probably Wrong

Let’s time-travel forward 100 years.

It’s 2120. You’re sitting in a college American history class, studying the late 1900s.

“Today, we’re covering the Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade that allowed abortion. I’m just going to warn you, the book I’ve assigned for this week is pretty graphic. If you want, you can skip over chapter 3. It covers Dilation and Evacuation procedures and how they eventually became outlawed in the U.S.”

A student raises their hand.

“I was just wondering, did people actually know what a D&E was? Did doctors just not tell them they had to like… rip the baby apart, one limb at a time?”

“Oh, it got worse than that,” the professor replies. “The governor of Virginia suggested babies could be denied medical care after birth if they were nonviable outside the womb.”

“That’s disgusting,” the student says. “I mean, if I were in that situation, I’d at least consider adoption. But I could never treat another human being that way.”

It’s Not Hard To Imagine This Scenario

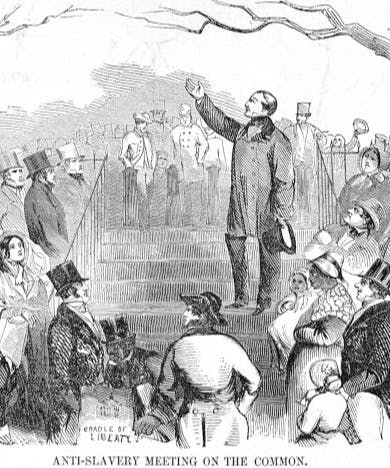

We see people making moralistic judgments like this all the time today, not with regard to abortion, but with regard to human rights abuses of the past, like American slavery. People vigorously claim they would have defended the vulnerable and helpless, even when it was unpopular to do so, and they make every effort to associate themselves with social justice movements of the past.

The irony is, these social justice advocates are often the same people who ignore — and even encourage — modern-day human rights abuses like abortion.

People make every effort to associate themselves with social justice movements of the past.

Would you have been an abolitionist in the South?

In a recent Twitter thread, Robert P. George, professor of jurisprudence at Princeton University, described the phenomenon.

“I sometimes ask students what their position on slavery would have been had they been white and living in the South before abolition. Guess what? They all would have been abolitionists! They all would have bravely spoken out against slavery, and worked tirelessly against it.”

The truth is, George continues, speaking out against slavery in the American South was extremely unpopular. Supporting abolition would have damaged one’s reputation, relationships, and career opportunities. Most people today probably would have remained silent on the slavery issue and simply kowtowed to cultural norms, just like people did back then.

It’s the same way with abortion. Just like in ages past, a certain class of people is not seen as human beings because, to another class of human beings, it’s politically, socially, or economically advantageous to think of them as non-humans.

Abortion is a modern-day human rights issue.

In the next century or two, we may see a societal shift occur on abortion, similar to that on racial justice, where it becomes reputationally advantageous to speak up for an unborn baby’s human rights. Someday, a professor may ask his class whether, if they had worked in Hollywood, Silicon Valley, or a number of America’s public universities where administration, faculty, and students favor abortion, they boldly would have defended the pro-life cause — and the class will assertively raise their hands, completely disregarding the social pressures of the previous era.

Unfortunately, Caving to Social Pressure Is Human Nature

No one put it better than Frederick Douglass, an African-American who escaped slavery in 1838. He understood that culture influences people’s thoughts and actions more than they’d often like to admit.

In The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Douglass writes about visiting his former master on his deathbed after slavery was abolished. He says if he had made the visit earlier in his life, it would have been very difficult, due to the horrific abuse he suffered.

Culture influences people’s thoughts and actions more than they’d often like to admit.

“He had struck down my personality,” Douglass writes of his former master, “had subjected me to his will, made property of my body and soul, reduced me to a chattel, hired me out to a noted slave breaker to be worked like a beast and flogged into submission, taken my hard earnings, sent me to prison… and had, without any apparent disturbance of his conscience… pocketed the price of my flesh and blood.”

But years later, Douglass came to a striking realization: His master was no less a slave to his society’s values and ideas than he was. When Douglass finally came back to visit his former master, he was able to recognize his master as similar to himself.

“He was to me no longer a slaveholder either in fact or in spirit, and I regarded him as I did myself, a victim of the circumstances of birth, education, law, and custom” (emphasis added).

Society is great at making the most egregious sins seem like acceptable customs.

Most people view American slaveholders as the pure incarnation of evil. But individuals like Frederick Douglass have the humility to realize that society is great at making the most egregious sins seem like acceptable customs. If the roles were reversed, it’s doubtful that Douglass himself would have been the fierce abolitionist that he became as a former slave.

Many Americans Falsely Understand What It Means To Be “Counterculture”

Today’s so-called “social justice warriors” often associate themselves with racial justice movements of the past. The truth is, unlike the Abolition and Civil Rights activists, Black Lives Matter and Defund the Police protesters receive little to no opposition from elite sectors of society. American institutions and city governments support them, and a plethora of major companies recently donated to racial justice causes. In fact, The New York Times pegged Black Lives Matter “the largest movement in U.S. history,” with 15 to 26 million Americans having participated in demonstrations over the death of George Floyd.

It takes little courage to stand up for a movement that encounters little to no opposition. Civil Rights, on the other hand, was counterculture. Abolitionism, if you lived in the South, was counterculture. Participating in those movements could get you spat upon, injured, or even killed. During those eras, it took actual guts to stand up for social justice.

It takes little courage to stand up for a movement that encounters little to no opposition.

Today, people are held in sway to their culture just as much as they were in America’s early centuries, picking and choosing which human rights abuses they call out, based on what’s socially acceptable. They may raise a clamor when someone dies unjustifiably at the hands of a police officer, but they’ll stammer when asked whether there’s an objective point at which a fetus becomes a human life.

Closing Thoughts

There’s no telling whether defending the rights of the unborn will one day become mainstream. We can only hope that more people will throw off the stranglehold of societal norms to speak up for human rights — even those that are unpopular to recognize.