Betty Crocker's Response To The Housewife's Plight Was To Build Community, Not Tear Down The Patriarchy

Betty Crocker, the beloved symbol of the quintessential poised and happy 1950s housewife, stands as the antithesis to Betty Friedan’s "The Feminine Mystique."

Even today — nearly six decades after the release of Friedan’s book — the two can be regarded as representations of the most prominent (and polar opposite) views on wifehood.

The Feminine Mystique, published in 1963, challenged the then prevailing ideas about male and female roles in society. Betty Friedan’s book explored the notion of women finding fulfillment outside of the home — a notion quite contrary to what women had been doing during the past decade. Friedan asserted that the 1950s housewife was silently unhappy with her relegation to the home and needed to claim her independence by entering the workforce, becoming politically active, and dismissing marriage and motherhood as patriarchal oppression.

Betty Crocker Supported and Affirmed Women in Their Homemaking Role

Betty Crocker, a fictional figure conceived in 1921 by a flour milling company (the Washburn-Crosby Company), was — and still is — the paragon of the women on whom Friedan based her best-seller. She quickly became an almost maternal figure in the kitchens of women across America, offering sound advice on baking and cooking. By 1945, she had become so popular that Fortune magazine named her the second most popular woman in America, behind First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Betty Crocker was the second most popular woman in America in 1945, trailing the first lady.

While Friedan told women that the root of their unhappiness could be traced to their situation as “prisoners” of the patriarchy, the Crocker figure identified a different problem: women were not being affirmed in their important roles as wives and mothers.

The Betty Crocker American Home Legion

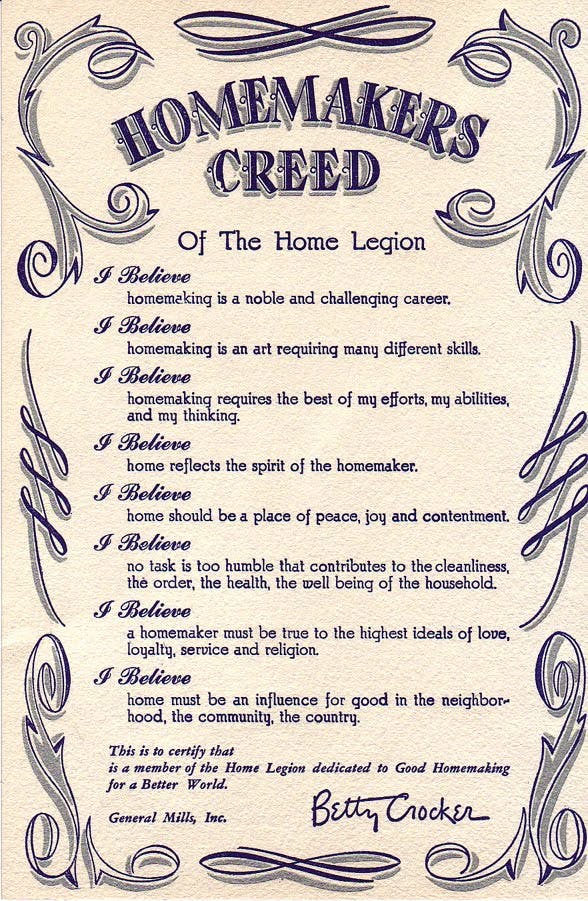

In response to the woes that homemakers outlined in letters to Betty Crocker, the Betty Crocker American Home Legion was established in 1944. Its purpose was twofold: to celebrate the vital work of childrearing and homemaking, and to create a community of women that could bolster each other up in this work. The legion was free to join, and each member received a copy of the Homemaker’s Creed.

By the late 1940s — even in the midst of World War II — over 70,000 women had joined the Betty Crocker American Home Legion. The creative mind behind both Betty Crocker and the Legion, Margaret Husted, stated that “good housekeeping is an art, and it’s about time it is treated as such.”

“Women needed a champion. They needed someone to remind them that they had value.”

Later, after her retirement, Twin Cities Magazine interviewed Husted about the noble project. “Women needed a champion,” she told the magazine. “Here were millions of them staying at home alone, doing a job with children, cooking, cleaning on minimal budgets — the whole depressing mess of it. They needed someone to remind them that they had value.” The Legion was a clear success, providing women with the support they needed for a trying situation in a trying time.

Betty Friedan Tried To Liberate Women by Encouraging Them To Be Less Womanly

The Crocker solution to women’s hardships effectively reached the core of the problem. Friedan’s proposed solution entirely turned the natural order of things on its head. Rather than championing women, Friedan encouraged them to completely turn against their female nature so as to find “happiness” and “fulfillment.”

In her book, Friedan wrote, “Gradually, without seeing it clearly for quite a while, I came to realize that something is very wrong with the way American women are trying to live their lives today.” She goes on to critique the very idea of femininity, writing, “When one begins to think about it, America depends rather heavily on women’s passive dependence, their femininity. Femininity, if one still wants to call it that, makes American women a target and a victim of the sexual sell.”

Friedan believed that femininity should be scorned and traded for something more masculine.

Instead of inspiring women to embrace their femininity as Betty Crocker did, Friedan believed that femininity should be scorned, buried, or traded for something else — something more masculine. Thus, there is great irony in her attempt to stand up for women. She actually ended up slandering womanhood with her assertions that, to be happy and free, one had to become more like a man.

Closing Thoughts

The world would descend into great chaos if the attempted fix for dissatisfaction or unhappiness was always to seek out a new identity, overturn natural order, and denounce that which is inherently good. This is what Betty Friedan proposed: rid the world of femininity, despite its innate goodness and necessity to society.

Thankfully, Betty Crocker offered a more sound option: lend strength and heart to that which, albeit difficult, is good. Neither the patriarchy nor the matriarchy needs (or ever needed) tearing down; both need to be built up so as to support a thriving society in which true masculinity and true femininity function harmoniously. Betty Crocker and her American Home Legion did wonders to ensure the building up of womanhood, and for that, we are grateful.