Hulu's "Harlots" Is A True Feminist's Worst Nightmare

A playwright friend of mine recently offered some professional advice: “If you don’t write the stories you want to write, then there are men who’ll only be too happy to write them.”

The arts, as with most societal forums, has been male-dominated from the beginning. Steadily, we've caught up, giving the world the truth about being a woman straight from the proverbial horse's mouth.

Period dramas are a prominent vehicle for this; there's been a spate of recent series dedicated to reevaluating history from a feminine perspective. However, often these portrayals of women designed by and for women fail because they recycle the negative images perpetuated by male writers.

The Female Gaze = Objectification

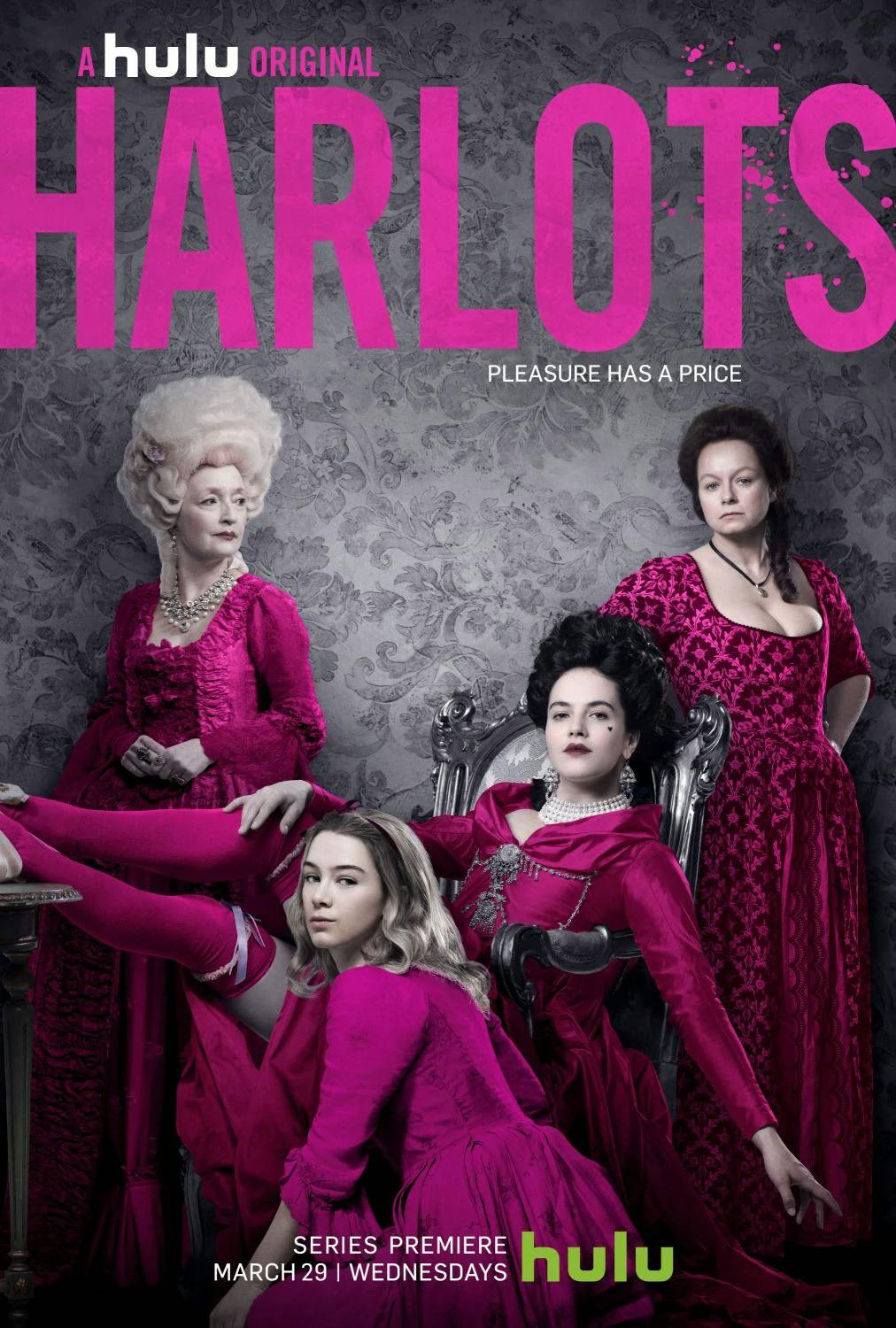

The show Harlots is a case in point. It's set in eighteenth-century London, centered around two brothels, one upscale, one poorer, and the women who work in each. These ladies are portrayed by an army of talented actresses, both period drama veterans and newcomers.

The show is produced by a woman, Alison Owen; it was created by two women, Alison Newman and Moira Buffini, and it's based on a historical book, The Covent Garden Ladies, written by a woman, historian Hallie Rubenhold. So far, so 'girl power.' Initially, the writers touted the series' lack of objectification of women, declaring that there would be "no male gazes" to aestheticize the characters' occupations. Instead, the series would be from a "whore's eye view," providing the women's perspectives.

Women as Sex Objects

Despite the creators' intentions, they still objectify their actresses by portraying them as sex workers on the job. Viewers see them doing it, which solidifies the mental equation of women with sex, thereby perpetuating the misogynistic stereotype of women as sex objects. On a more concerning note, these scenes objectify the harlots' lifestyles by making them seem desirable.

These scenes objectify the harlots' lifestyles by making them seem desirable.

Because of their allure and tenacity, these women have power over men and each other – what woman doesn't want some degree of influence? Though it's marvelous to see so many resilient, clever women onscreen, most of their strength is derived solely from their sex appeal, which debases their humanity. Besides, there's a lot of misery for them as well. Some of it is probably intensified for the sake of conflict, but there are definite drawbacks to their lifestyle (heartbreak, illegitimate children, and STDs, to name a few), as there indeed were for these women.

Being Sexually Degraded is Apparently "Liberating"

However, the show glosses over all this degradation as 'liberating.' Jessica Brown Findlay, one of the leading ladies, describes the 18th-century milieu in an interview: "If you were married your body was considered the man's property, along with your actual property. So anything could be done to you... The harlots' property is theirs. It's their body. And they decide what happens to it, to a certain extent."

"Prostitution as empowerment," the interviewer remarks.

And yet, it's a false sense of empowerment; prostitution drags women down to the lowest level of existence, becoming mere punching bags for men to work out their emotions which they process via sexual activity. What's more, the notion of female agency rings hollow when contrasted with the onscreen couplings.

Prostitution drags women down to the lowest level of existence.

Autonomy includes interacting with others on one's own terms, with confidence and a sense of appropriateness. More often than not, the women are victimized by their clientele, and, even more disturbingly, one another; hardly an encouraging spectacle for female viewers.

Predatory Women – and Men

The most distressing aspect of the show is the lack of genuinely good male characters; all the men are either abusive, idiots, cowards, awkward, or dull.

Although I disagree with most of this Paste article, the writer succinctly echoes my frustration, calling the series "a self-indulgent, wish-fulfillment-driven universe in which rich white men must be demonstrably and catastrophically evil, the poor are nearly always virtuous, every woman is smarter and craftier than every man, everyone is a victim of sexual abuse (like, everyone), anyone pious is either a hypocrite or a simpleton, and anyone from a downtrodden or marginalized demographic is unflaggingly noble (unless they are also wealthy, in which case they go directly to evil, unless they are the sex abuse victim of someone even wealthier)."

It's certainly a wish-fulfillment scenario for the radical feminists who see men as lesser than women. The absence of upstanding men contradicts history; in that era, there were many good-hearted souls, both men and women, who sought to reform the plight of the destitute – for starters, check out Thomas Coram.

It's certainly a wish-fulfillment scenario for the radical feminists who see men as lesser than women.

The Show Treats its Actresses Well

On a more positive note, the set full of women has proved to be wonderfully nurturing, according to the actresses. In a Cosmopolitan interview, Ms. Brown Findlay (who plays Charlotte Wells) described her experiences when it came to the intimate scenes:

" made me feel so secure. I was able to say exactly what I wanted to do and didn't want to do, what I was happy with... That's amazing, that never happens — you normally have to chisel away at what you do and don't prefer to do. On set, it was very accepted that you could change your mind and that's OK, it should be that way. It was the safest, most supportive way of working that I've ever experienced."

Jessica Brown Findlay as Charlotte Wells

The on-set feminine camaraderie clashes strongly with the onscreen viciousness. Headlines praise the series as the "feminist costume drama of your dreams" and being "about women helping women," but in fact, backstabbing outweighs benevolence.

When things get physically or emotionally brutal the women match the men in evil, stride for stride, ruthlessly taking down their male abusers and female rivals. In canine terms, the world of these Georgian brothels is a bitch-eats-bitch society, and the women's behavior adds fuel to yet another stereotype: the vengeful female.

The women's behavior adds fuel to yet another stereotype: the vengeful female.

A Missed Opportunity

While I applaud Newman and Buffini's care for their actresses' comfort, it's evident that they missed the opportunity to tell a beautiful, uplifting narrative. Girls sometimes made it out of the trade. One of the women on the series, Marie-Louise, a refined French prostitute, makes her getaway early in season 2 and is never seen again.

Poppy Corby-Tuech as Marie-Louise D'Aubigne

Why not follow girls like her, who break free from the system, instead of perpetuating the cycle of despair, and reinforcing degrading stereotypes of womankind? I'm not saying we shouldn't create fiction based on these historical narratives – we ought to deal with the darker parts of our past because they hold so much we can learn. But there's a way to tell these stories without overemphasizing the sordid aspects; to reduce anyone (dead or alive) to a single aspect of their being does them a huge disservice.

Prostitution as Desireable

Newman and Buffini set out to normalize these women by portraying their jobs as everyday occupations. In doing so, they only succeeded in making prostitution desirable, when in fact no woman would choose to demean herself to such a level.

Put simply, it's a glamorization of human servitude. Furthermore, the best way to normalize the girls would have been to never show them on duty, always off. We know what they do – show us their interior lives, not their flesh.

Put simply, it's a glamorization of human servitude.

These quotes from a review in The Guardian nicely encapsulate my thoughts on the series: "For all the talk of female autonomy, the characters are thinly drawn and, when all is said and done, this is a show about humping... A feminist masterpiece it ain't."

The show may be the stuff of radical feminists' dreams, but it's a true feminist's nightmare. Real feminism celebrates both men and women, delighting in their unique complementary gifts. This truth was knitted into the fabric of past societies, and the narratives we set in those pasts should reflect it.

The show may be the stuff of radical feminists' dreams, but it's a true feminist's nightmare.

Stories of Hope

Even if a certain tale is gritty in nature, with flawed characters aplenty, there must be some scrap of hope. After all, that's what period dramas do best: provide heartwarming endings in the face of hardships.

The heroine struggles through her adversities, conquers her inner demons, and gains the victory. As she smiles to herself at the journey's end, we know she's destined for happiness.